1871-1889

Phoenix Rising from the Ashes

In 1871, Chicago was a shell of itself — the Great Chicago Fire had ravaged the city and destroyed buildings, displaced thousands of families, and claimed hundreds of lives. Many of the structures in the city were made of wood at the time, which only served as kindling for the fire. That coupled with the winds coming from Lake Michigan created perfect conditions for the flames to prevail and spread rapidly. The unrelenting fires consumed everything that was in its path, which devastated much of the city center. Unfortunately, the events following the Great Chicago Fire were no less difficult. In 1874, another fire spread and burned through the Loop area of the city. Three years later in 1877, the United States experienced the Great Upheaval — a series of strikes and civil unrest from the working class, specifically in the railroad industry, demanding fair pay, hours, treatment, and conditions. This labor movement greatly affected the city of Chicago, and in 1886, the built-up frustrations of the working class led to the Haymarket Riot. These are just a few examples of the challenges during this era of time. Unfortunately, this concoction of unfavorable events sullied Chicago’s reputation to the rest of the world, but the city was not discouraged. What followed was an astonishing rebuilding process that ushered in a boom of economic, cultural, and civic prosperity for Chicago and its citizens. Chicago restored and remodeled itself quickly, and at the epicenter of this movement came the building of the Auditorium, an architectural gem that marked the beginning of a new era for Chicago.

The Vision

The 1871 and 1874 infernos took with them several buildings including Chicago’s first opera house which was built in 1865. Despite the loss of the venue, opera was a beloved artform to Chicago and the city made do with what it had to keep opera alive. Installations of temporary opera houses sufficed for a period, but it became obvious that a city that loved the arts so much needed a permanent house dedicated to it. After Chicago’s Grand Opera Festival in 1885, businessman, philanthropist, and arts patron, Ferdinand Peck, began planning the Auditorium. He envisioned a theatre that would serve all and promote unity across class and cultures. His vision comes from his belief that the arts are important for all of humanity because it can positively influence the way individuals think and behave. He saw the arts and by extension, the Auditorium, the solution to rebalance and uplift the citizens of Chicago from the turbulent years that they have faced. Peck enlisted the architectural expertise of Dankmar Adler, Louis Sullivan, and Frank Lloyd Wright to help bring his plans to fruition.

Ferdinand Peck’s good-natured intent for the Auditorium did not come easily. The cost for the construction of the Auditorium was exorbitant and for a theatre that functioned under the principles of inclusivity was likely to see little returns and only a growth in expenses as observed by other great halls in the country. Cincinnati Music Hall, and New York City’s Metropolitan Opera House being leading examples of the financial sacrifice needed to sustain such structures. However, Peck was compelled to move forward with this colossal task because he believed that the people of this city were worthy and deserving of it.

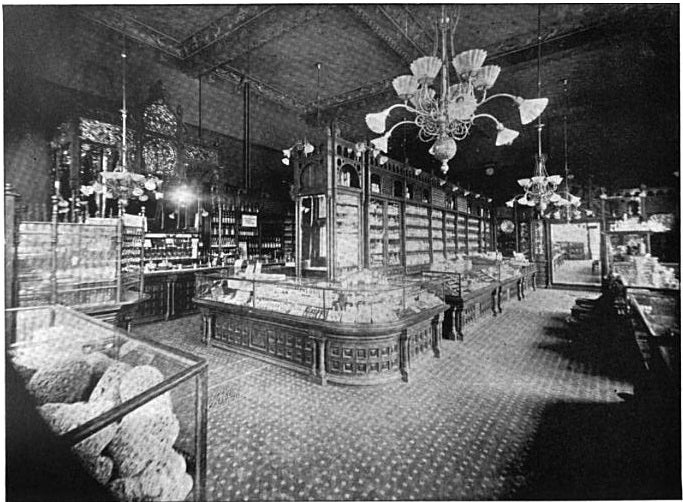

To mitigate the accrual of expenses, the Auditorium Building also served as a hotel and office. The idea behind this design was to have the hotel and office be the primary sources of revenue for the Auditorium, which will help fund the performances at the theatre while also keeping ticket prices low. The original vision for the Auditorium included a 4,200-seat theatre surrounded by over 130 offices, a first-class 400-room hotel, a public bar, pharmacy, and restaurants.

The Architecture

When walking into the Auditorium, it is difficult to not gasp at the theatre’s remarkable beauty and mammoth scale. The iridescent lights reflecting off the sweeping arches that surround the stage, and the elaborate ornamentation that decorates every aspect of the theatre are only some of the elements that make the Auditorium Theatre breathtakingly stunning. Louis Sullivan’s nature inspired ornaments and motifs pays homage to the natural cycle of the seasons and life as a whole. The abundance of man-made flowers and leaves is suggestive of the natural world’s persistence to be reborn, no matter the tragedy or end that came before it — a fitting theme for a theatre that was only able to exist because of the difficult circumstances that preceded the opening of the theatre. But the Auditorium is so much more than just a pretty face. It is the theatre for all the people of Chicago, a place where every resident and visitor to this region will always feel welcomed.

Since the theatre’s beginning, it has aimed to create an inclusive space, and this principle is reflected in the arrangement of the Auditorium’s seating and layout of the theatre. Traditionally, box seats occupied the best space in theaters around the world such as the Metropolitan Opera House. Instead, the Auditorium adopted a seating model that would be less class divided and thus the theatre was originally designed without box seats to remove the privileged seats that were normally reserved for the wealthy (the box seats were eventually added to the blueprints before the theatre’s opening after receiving several requests). This intentional design encouraged equality amongst Chicagoans by giving the middle and working class the same rich and elegant experience that would otherwise be only accessible to those who could afford it. Additionally, thanks to the incredible interior design by Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan, the theatre is known to have near-perfect acoustics and be visually pleasing in every seat.

When the Auditorium Building was first constructed it was the tallest building in Chicago and the largest in the United States. It had the newest technology available at the time, which included incandescent light bulbs and central air conditioning — a huge accomplishment and luxury during a time when electricity was not available in every household yet. The theatre was also equipped with the Frank Roosevelt No. 400 organ, which had its pipes hidden behind the decorative half circles that are at both sides of the stages. Externally the building is Richardsonian Romanesque by design with its large pillars, massive stone walls, and semicircular arches, but inside is unmistakenly American, more specifically Chicagoan.The architecture, decorations, engineering, metal work, wood carving, and mosaic floor, all owe its inceptions to the Chicagoans that brought it to life. Much of the Auditorium building is made of granite and iron, and the iron work that is masked by artwork that sits on top of it is just as elaborate and intricate if unveiled. The Auditorium, then as now, was a marvel of engineering and architecture, and was undoubtedly centuries ahead of its time.